Beneath the Veil of Dictatorship: Duty of Remembrance in Chile

- Eleonore Dlugosz Donnen

- Nov 15, 2025

- 10 min read

With the Chilean presidential elections being held tomorrow, November 16 will be an important day for Chile. A Marxist communist president may be elected, the first since Salvador Allende (1970-1973); his legacy brings back painful memories to the coup d’état before the violent dictatorship. To honor and remember the victims of these frightful years, a museum was created, instilling their legacy in a national one. I will showcase the archives of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights of Santiago de Chile; what has been done, what is remembered, and what you can observe.

El Museo es una Escuela / The Museum is a School

Although the museum was proposed by President Michelle Bachelet in 2007, it was not inaugurated until 2010. Following the recommendations of the victims' families and human rights organisations, it is a place where extremely valuable archives declared “Memory of the World” by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) are kept. Located in Quinta Normal, it is easily accessible with a station located just below the museum. Not only physically accessible, the museum is financially accessible with free admission.

In recent years, the museum has established itself as a place where the duty of remembrance happens with organized school visits. On the two occasions I visited, I saw numerous school groups that came to learn about a bygone era that is still present in the minds of Chileans. At the entrance to the museum, you will find an inscription that states “El Museo es una Escuela” (The Museum is a School).

Everyone who enters the museum is invited to learn about the history of Chile, whether you are Chilean or not. Once you exit, you will not be the same person as you will have absorbed the political memory of a state that went under dictatorship and on the consequences it had over its population.

Golpe de Estado / Coup d’Etat

Before providing information on the numerous aspects of memory and dictatorship covered by the museum, it is important to establish some context. In 1970, Salvador Allende, a socialist, became the first Marxist president elected in Chile. He carried out numerous radical reforms, such as policies to nationalize copper, a material that is very abundant in Chile. The Chilean elites and the right wing rejected his reforms, and opposition grew more and more. It is also important to mention that, during the Cold War era, the United States viewed a Marxist president with suspicion, and the CIA may have allegedly greatly destabilized the country. While the date of 11 September immediately brings to mind in the common psyché the tragic terrorist attacks in the United States, it is also a difficult date for Chileans.

On 11 September 1973, the Chilean army, led by General Augusto Pinochet, launched a military coup. La Moneda, the presidential palace, was bombed. Allende officially committed suicide, and at that moment the army took control of the capital, the congress and the entire country. A military junta led by Pinochet was established, and opponents were arrested, tortured and executed. Censorship was total, a curfew was imposed, the constitution suspended, and the country underwent a shutdown. Pinochet established a military dictatorship that lasted until the 1990s.

When you enter the museum, you will have to climb a few steps before finding yourself facing the newspapers announcing Allende's death (Photo A). Next to them, you will find the rare existing photos of the military's arrest of civilians (Photo B, C). The museum is structured chronologically. From the first floor onwards, you will be immersed in this coup d'état, although this first section is factual and does not seem to treat the historical events from a particular angle. History is presented through a historical lens, but the photos and videos of the Chileans who were arrested will have a lasting impact on you. You are witnessing a military junta.

Asi se Tortura en Chile / This is How They Torture in Chile

Torture, unfortunately, a well-known feature of dictatorships, is no exception in Chile, and the entire central section of the museum's first floor is devoted to this subject: the disappeared. This included those who were deported to torture camps, but also the survivors, those who remained alive and were willing to testify. On several occasions in the streets of Santiago, I often came across photos of the disappeared, victims who were never found and for whom the people continue to demand justice (Photo D).

A very powerful section of the museum deals with this subject, featuring videos of survivors' testimonies alongside videos showing schematic representations of the methods of torture used. It was in this section that I saw the most tears, the saddest looks, a pain that has not yet passed, that of a people scarred by the violence imposed on them. As hard as these videos are to watch, they seem necessary. Let us not look away from the atrocities committed, let us face up to the torture suffered, let us remember.

The Chilean torture network, well organized into numerous camps, could also count on other intelligence agencies in the Southern Cone. Called ‘Plan Condor’, the Chilean dictatorship coordinated with the intelligence services of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, which were also under dictatorship, to eliminate all potential threats. The threat of torture was not national but extended far beyond the Andes mountain range.

While the violence depicted in the archives concerning torture seems difficult to bear, if you look up, you will see their faces (Photo E). The museum has hung more than a thousand photos of the disappeared, the victims. A powerful sight for visitors, all these faces, all these people who were victims of state abuse. The wall is three floors high and runs the entire length of the museum. These faces are omnipresent; no matter where you are in the museum, you will see them, you will be surrounded by them. A constant reminder of the consequences of dictatorship. On the second floor, you can digitally browse the entire wall, and when you touch a face, you receive information about that person: their name, and what happened to them.

Mujeres Detenidas / Detained Women

Among the sections on torture victims, there is a section dedicated to women who have been tortured. Tears surged as I watched videos against a black background, with women recounting how they lost their babies during torture sessions and describing the sexual violence they suffered.

Political violence, such as torture, takes on a more personal dimension when the body is attacked sexually. Repeated sexual abuse, beatings, insults, threats, even simulated hangings for some, numerous books can be read about the abuse on women (Photo F).

These heartbreaking archives also contain a section on pregnant women. According to figures from the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture (Valech Commission), more than 229 pregnant women were arrested (Photo H). Some gave birth in detention, while others suffered miscarriages or abortions as a result of torture (Photo G). For victims of sexual abuse, it is very difficult to talk about the crimes they have suffered, and when political torture is added to the equation, resilience becomes even more difficult. Women experienced the torture of the dictatorship differently from men, and the fact that the museum focuses on their cases shows that the duty of remembrance, while rooted in collective memory, still takes care to incorporate the numerous narratives that exist.

Asilo, Exilio / Asylum, Exile

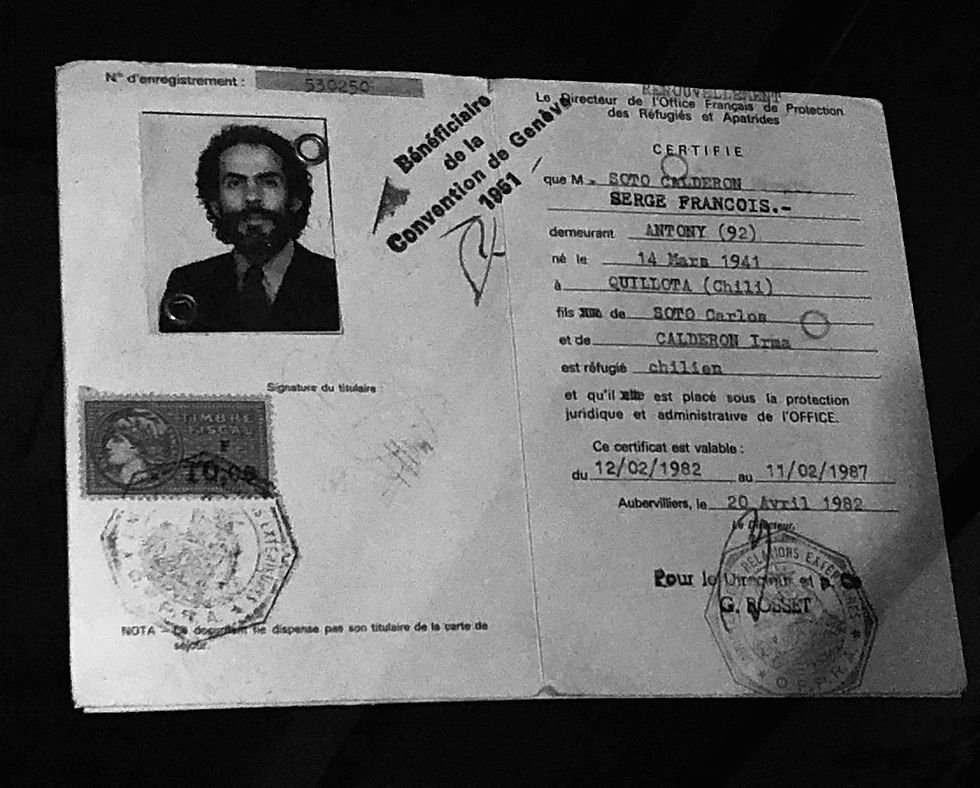

While the dictatorship had an internal impact on the population, its consequences are felt internationally. The entire second floor is dedicated to Chileans in exile around the world. Legal Decree 81 of 1973 authorized the military junta to expel people from Chile while prohibiting those who had already left Chile from returning. This diaspora acted as a psychological destruction, separating families and losing friendships. Numerous archives show the exile of Chileans to Italy (Photos I, J), while others benefited from the 1951 Geneva Convention on the Status of Refugees (Photo K).

Extensive research has made it possible to identify how many refugees each country took in. For example, Switzerland took in 2,500 Chilean refugees, France 7,000, and Italy initially had 207 refugees in 1974, but 10 years later, in 1984 nearly 12,000 Chileans had joined the Mediterranean country. The museum honors those who remained and suffered under the dictatorship internally, while celebrating the narrative of those who fled the terror of the dictatorship.

La Noche del Plebiscito / The night of the Plebiscite.

"No me voy, no importa lo que pase."

I’m not leaving, no matter what happens.

Augusto Pinochet, when he realized he had lost the Plebiscite in October 1988.

Towards the end of the exhibitions on the second floor, you will find information about the plebiscite that took place in 1988. Following a constitutional law passed in 1980, this referendum asked citizens to vote yes or no on extending Pinochet's term of office. This paradoxical law was intended to give Augusto Pinochet a form of legitimacy for his next term, but in fact proved to be an escape for the Chilean people to democratically contest a second term. With the “NO” vote clearly winning the referendum, Pinochet had to leave power.

This section of archives is very valuable because, beyond the important nature of the plebiscite, it contains intelligence documents. Declassified information from the Defence Intelligence Agency and US military intelligence provide insight into how Pinochet reacted to the collapse of his power plans. On the eve of the plebiscite, Pinochet had contingency plans to sabotage the plebiscite by nullifying the electoral process if the government was losing the referendum (Photo L). Plans that would have encouraged serious and widespread bloodshed, another cycle of disorder, to make sure that Pinochet stays in office. The declassified documents also attest that in September, a month before Ambassador Harry Banes alerted the State Department about Pinochet and the risk of violence and terror if he were to lose. Intelligence reports ultimately reveal that although Pinochet was prepared to fight immediately in order to retain power, his advisers and the Chilean army refused to follow him (Photo M). On the night of the plebiscite, Pinochet had to accept that he had lost power.

These documents accurately document Pinochet, how he reacted and left power, a liberating night for Chile. The museum shows that every key stage in Chile's history is documented, and the variety of documents is impressive, whether it’s photos, videos, letters, passports or even declassified intelligence documents.

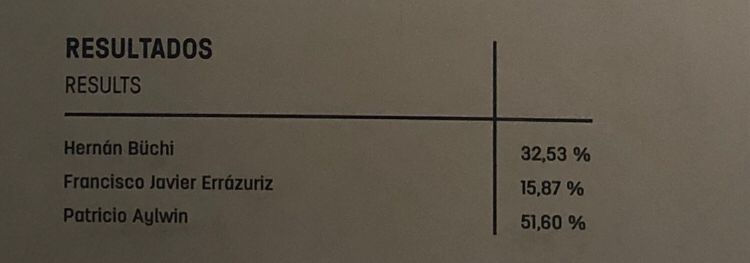

Gana la Gente / The People Win

The second floor of the museum concludes with a section detailing the end of a dictatorship and the emergence of new hope for democracy. With Pinochet leaving power, new elections had to be organized in Chile, this time establishing a return to democracy. These elections took place in 1989 and three men competed: Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin against Hernan Buchi, supported by the Radical Democratic Party and the Democratic and Progressive Pact, and finally Francisco Javier Errazuriz, a businessman representing himself as independent of any party. The results were clear: Patricio Aylwin won with over 50% of the vote (Photo N), marking a new turning point in Chilean political life, the institutional end of military dictatorship and a long-awaited return to democracy. After more than seventeen years of repression, the people won. The country could rebuild itself on civic foundations.

This last section marks the end of the museum's permanent exhibitions. However, the visit does not end there, and on the third floor you will find temporary exhibitions that deal with memory in a more artistic way, less focused on Chile's historical and political narrative.

Ni tan Dictator, ni tan Santo ? / Neither a Dictator, nor a Saint?

While this museum fulfills the duty of remembrance by documenting the atrocities committed by the dictatorship, the exiles, the tortured, and the censorship, the figure of Augusto Pinochet still represents a conflicting part of Chilean memory.

The museum takes the side of the victims and portrays Augusto Pinochet as the villain of the story. However, some people continue to believe that Pinochet did what was necessary, that he was a leader who lifted the country out of the crisis into which Salvador Allende had plunged it. While you can find posters on the streets calling for the search for and justice for the disappeared, you will also find pro-Pinochet graffiti. Some continue to believe that Pinochet taught the socialist a good lesson, while others associate Pinochet with genocide and violent dictatorship (Photos O and P). The different graffitis are the perfect portrayal of the different memories that exist, one that elevates Pinochet as a leader, the other as a criminal. To have a coherent and comprehensive understanding, the museum must therefore be seen as a tool that serves the duty of remembrance, but not as the sole narrative of Chilean memory.

It is impossible for me to convey all the emotions you might feel, all the archives you might see for yourself. But this museum, more than a place of remembrance, is a place where all the narratives of the victims of the dictatorship come together. This museum is to honor, to remember the Chileans of the past and to help overcome the sore memory of the Chilean of the present.

More than a simple duty to remember, it is an essential act for a country to be able to move on, to turn a heavy page where black ink is indelible on the spirits of its people, people who are strong and resilient and who will not forget the dictatorship.

All photos were taken by Eleonore Dlugosz Donnen at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, the Cemetery of Recoleta, or in the streets of the center of Santiago de Chile between August and October 2025.

Comments