A New Genre of Film: Revolutionary Stitched Resistance - FASHIONCLASH 2025

- Azura Kooistra

- Dec 1, 2025

- 14 min read

Trigger Warning: This article discusses films that include themes of gender-based violence, self-harm, bodily transformation, blood, horror and gore imagery, ritualistic violence, religious symbolism, and queerphobic behaviour. While graphic details are not described, some content may be disturbing or emotionally triggering for readers.

A Red Glow, A New Kind of Cinema

FASHIONCLASH 2025 has proven itself a turning point in European fashion film, defined by outspoken, genre-bending works that centre feminist rage, queer voices, and bodily transformation. This year’s films mark a decisive shift: not fashion as spectacle, but fashion as political cinema.

On 14 November 2025, six finalists were screened alongside two FASHIONCLASH-produced premieres, followed by the Fashion Film Award and Kaltblut Award ceremony as part of the Fashion Film Program.

The event took place at Lumiere in Maastricht, in one of their cinema rooms. The red interior was illuminated only by the screen’s glow. Hums of multilingual conversations dominated the air, paired with comfort. Dutch, German, English, French, Czech, Indonesian, Russian, and more could be heard, filling the event with multicultural, youthful energy. It was an intimate, ceremonious atmosphere, especially with the cluster of unique and alternative styles worn by the audience, particularly amongst the young. Older couples attended as well, on an arthouse date night, with events like these seeming to be the go-to. It soon became clear that the majority of the young participants were the teams involved in the films’ creation, excited to see their work on screen and anticipating who the winners would be.

But it was during the event’s introduction, before the films reached the screens, that one thing was made clear: we were watching a new chapter of FASHIONCLASH unfold. The organisers repeatedly described the films as “beautiful” and "outspoken", signalling a striking shift from previous years. In fact, one of the organisers described the previous years’ focus on fashion and event production in documentary-style films as “meh”.

While politically charged fashion films have been emerging in recent years, including last year’s Shame, this year’s six finalists mark a more prominent transition toward a new genre of narrative, politically charged, identity-driven filmmaking in fashion film. Fashion is now being used within the story, rather than as the subject itself. The Class of 2025 represents a new cohort with cinematic ambition, thematic cohesion, and formal experimentation, representing a new artistic identity: bold, confident, and politically conscious.

Below, I will break down the main themes I recognised across the films, namely the queer and feminine identities.

The Six Finalists

We start with Circle by Ferhat Ertan: a tense, intimate film about gender non-conformity, shame, and longing within a Muslim context. Arif, a tailor, secretly tries on a hijab while examining himself in the mirror. When his peer unexpectedly knocks on the tailor shop’s entrance, harsh light and judgment are brought to the screen. Arif quickly takes off the hijab and goes out of the closet (pun intended) to let the peer in. After being mocked for his red-painted nails, Arif’s peer asks and jokes about his queerness, laughing at the mere possibility. When the peer leaves, Arif injures himself with a sewing machine, possibly to justify the nail colour he couldn’t scrub off or as self-punishment. In the final scene, it is implied that Arif lies about needing more time to repair a customer’s dress so he can try it on himself. The film explores forbidden desire, internalised shame, and quiet acts of queer self-assertion.

You can buy a ticket to watch Circle here.

We then move on to Motherfocking Art by Marloes IJpelaar: a chaotic, comedic, and confrontational takedown of the male gaze in fashion photography. It starts with three models on a photoshoot who gradually realise that they are being forced into stereotypical, sexualised poses by an unseen male photographer who is dismissive, body-shaming, and ignorant of women’s realities, including periods. After a menstrual-cup mishap with one of the models and discovering that the photographer has been photoshopping them, all chaos breaks loose. The women rebel by feasting unapologetically on the buffet, destroying the set, and beating up the photographer. Finally, one of the models kills him (or at least suffocates him to unconsciousness) in an absurd, but very comical and ironic manner. The film ends with the women lying in a field, celebrating their body parts that are traditionally seen as not part of the beauty standard, rejecting them altogether, and reclaiming their self-image.

You can watch the Motherfocking Art trailer here.

Sticking with the same theme of feminism, we move on to one of my personal favorites and the winner of the Kaltblut Award, which is The Feminine Urge by Lilian Brade, Phuong An Phi, and Niclas Hasemann: A visually rich feminist horror film exploring female rage, monstrosity, mythology, sexuality, and the Madonna-Whore complex. For those who have a special place in their heart for absurd horror, like me, this film is a definite addition to your watch list. This film acted as a poetic anthology without spoken dialogue. It uses fabric, blood, religious iconography, body horror, and archetypal imagery to portray the monstrous feminine as powerful and multifaceted. Scenes include a bride stained with blood, an insect-toothed woman in a medical room, childbirth and umbilical cords, multi-breasted mythic figures, and a final monstrous procession leaking dark fluids. In an interview with Brade, she reveals her inspiration from femme horror, Christian symbolism, and her research on female archetypes to craft a visceral story of transformation, rebellion, and reclamation of the monstrous body.

You can watch The Feminine Urge here.

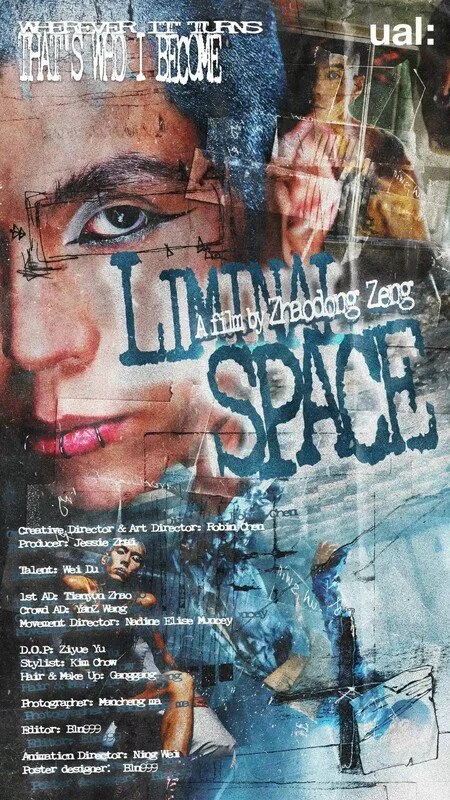

We then move away from the mythical and mystical to Liminal Space by Zhaodong Zeng: a mediation on alienation, identity instability, and queer self-discovery within an overwhelming modern cityscape. In this film, a Rubik’s Cube becomes a metaphor for shifting selfhood. It is first monochrome, then it is marked by a red line, then finally solved, only to be scrambled again at the end. But in between the scenes focused on the Rubik’s cube, the main character moves between fragmented realities, rave culture, techno chaos, and serene, blue-tinted scenes. The film blends live action, screen glitches, cyberpunk visuals, and animation to show identity in constant flux. Its ending, with the cube scrambled once more, signals the ongoing, unresolved nature of self-discovery.

Juxtaposing the flashing lights shown previously, we see the simple settings but complex themes of Scapegoat by Caspar Heijnneman and Daan Sanders: a fashion-thriller drama clearly inspired by the 2018 adaptation of Suspiria, exploring control, liberation, and mother-daughter power dynamics. One notable scene features the six daughters, dressed in skin-toned garments, manipulated through ritualistic dance and red ropes by the dominant central Mother figure, dressed in all red with eerie white eyes. The daughters eventually overpower her, covering her in clay and hay, leaving her dethroned and transformed. They walk away empowered, serving as an allegory of breaking free from generational authority and reclaiming identity.

You can watch Scapegoat here.

Finally, we have Do I?, the winner of the Fashion Film Award, by Salt Murphy and James Nolan: a romantic yet critical take on the queering of wedding tradition. Set in an old-money mansion with vintage aesthetics, the film follows an interracial gay couple on their wedding day. While portraying romantic intimacy and luxurious bridal fashion, it also raises questions about marriage as an institution, highlighted by a guest muttering, “Marriage is such a scam." We also get glimpses into the backgrounds of other queer couples, normalising queerness within a conservative setting. The film contrasts stability and uncertainty, tradition and queerness, ultimately exploring love within structures not designed for queer people. The jury particularly called this piece “emotional”, inspiring their choice.

You can watch Do I? here.

The Premieres

The two films HANGMAN & CO by Matti Paffen, Birsu Tamer, and Hedzer Seffinga, and The Sneeze by Yala Claessens, Vera van Nuenen, and Bent Lochtenberg were shown for the first time that night as well.

HANGMAN & CO is a black-and-white, stylised film centring on striking set and costume work. With a focus on denim as a representation of blue-collar jobs and paint, the film appears to explore identity, tension, and performance within our capitalist system. The set was excitingly displayed on the second floor of Lumiere, adding a new perspective to the film when seen in colour. One of the most creatively striking aspects of the film was the credits stitched onto the denim jacket itself, which was hung right next to the set.

The Sneeze is a surreal, playful, and slightly disturbing exploration of queer joy, bodily disruption, and transformation. The main character experiences growing discomfort that culminates in a sneeze so powerful it ruptures reality, violently reshaping their surroundings into a loud, unfamiliar world. Through movement, fashion, and exaggerated physicality, the film portrays queer liberation through taking up space, turning an ordinary bodily reflection into an ecstatic, disruptive, reality-bending event.

Queering the Frame: Identity, Desire, and Disobedience

Across the films, queerness is shaped by tension, particularly between desire and repression, stability and fluidity, and tradition and selfhood. Queer identity emerges not as a fixed essence but as a dynamic force continually negotiating repression, longing, and transformation. Fashion, in this sense, becomes the central medium through which this negotiation is staged. It is less as an aesthetic embellishment and more as an instrument of disobedience, reclamation, and embodied truth. Each film uses clothing and costume to challenge dominant narratives of gender, sexuality, and propriety, whether through forbidden garments, destabilised club aesthetics, and the queering of marital iconography.

We see, in films such as Circle, gender non-conformity suppressed by cultural/religious norms; in Liminal Space, identity dissolves and reconfigures through the use of the Rubik’s cube; in Do I?, queer love framed inside heteronormative wedding traditions; and in The Sneeze, pressure builds until it ruptures reality. Identity is never fixed. Instead, it is contested, hidden, scrambled, or bursting outward.

In Circle, fabric becomes the site where gendered repression and longing collide. The hijab and dress are not neutral garments, but forbidden fabrics, with cultural, religious, and sexual significance. When the main character fits into these fabrics, fashion becomes a dangerous terrain, where the monochrome palette and shadowed composition highlight how clothing becomes an illicit touchpoint with the self. This film argues that clothing can both reveal and incriminate, as seen by the peer’s focus on his red-painted nails: the garment is no longer a private act of exploration but a social indictment.

The main character’s self-harm with the sewing machine suggests that fashion is experienced as a transgression with spiritual and communal consequences, perhaps even interrupting religious rituals like ablution. Yet in the final scene, when the main character claims the dress for himself, fashion is ultimately shown to be a quiet form of queer insistence. Desire re-emerges stubbornly in the seams. It is an act of covert, trembling but deeply courageous disobedience.

Much like how Circle focuses on fashion as a representation of one’s identity, Liminal Space frames fashion as less about garments. On a different note, though, Liminal Space represents fashion through aesthetic atmospheres: clubwear, rave silhouettes, techno-inflected distortions. Through the fish-eye lens, blue hues, and cyberpunk glitches and animation, the whiplash-like visual styles act as a wardrobe of identities the protagonist slips in and out of.

Rather than stabilising identity, fashion contributes to its fragmentations, much like how the Rubik’s cube moves from blank, to singularly marked, to solved, then scrambled again. The film insists that queer identity is an ongoing process of misalignment and reconfiguration. The rave’s fashion is a visual rebellion against normative selfhood. In this world, fashion is neither a mask nor a revelation but a state change, a portal into fluidity. The constant switch between serenity and sensory overload mirrors the psychological whiplash of queer subjectivity navigating surveillance, desire, and dissonance. Fashion in Liminal Space goes a step further than Circle, dissolving rigid frames of identity entirely.

The Sneeze (although only part of the premiere rather than the six finalists) follows a similar sentiment of resistance through chaos, but in a more optimistic lens. Thus, rather than queer joy manifesting through solemn resistance, it manifests through surreal, bodily exuberance. The costuming included exaggerated silhouettes, playful textures, and garments that seemed almost to vibrate with vibrant colours. This all supports the protagonist’s transformation from discomfort into cosmic rupture. The sneeze itself functions as an involuntary queer eruption, a bodily refusal to remain contained.

The fashion in this film is used to exaggerate queer presence, paired with unpredictable movement, representing the protagonist’s refusal to shrink and contain themselves. The oversized garments and amplified bodily expressions also allow the main character to take up space in a way that may be unsettling, but liberating. This film insists that queerness can resist through absurdity, humour, and sensory overload. Fashion is the architecture of queer joy: unruly, disruptive, impossible to ignore.

Do I? moves away from the chaos of Liminal Space and The Sneeze to the stillness of marriage imagery. It frames its interracial gay couple within the hyper-traditional, old-money wedding aesthetics, including ivory mansions, manicured lawns, couture white garments, and vintage film textures. Opposing Liminal Space and The Sneeze, Do I? queers a visual vocabulary historically reserved for straight, upper-class couples rather than outrightly rejecting it. It is quite similar to the theme of conforming to gendered garments as representation of one’s identity in Circle, but Do I? questions the conformity of gendered and heteronormative traditions.

Fashion becomes the site where the film critiques the institution of marriage itself. The pristine suits and bridal-esque whites signal conformity, yet queer couple inhabits these looks with an intimacy that destabilises their hetero-coded history. The guest’s offhand comment, “Marriage is such a scam,” punctures the fantasy further, revealing the fragility of the institution even as the fashion attempts to uphold it. Thus, although the film does not directly throw out heteronormative traditions, it does expose the friction between appearance and ideology by placing queer bodies inside almost-traditional garments. Do I? does not necessarily conform, but bends the visuals with nontraditional cake-cutting, signing on-site, and unconventional outfits. In Do I?, fashion is used to question: who marriage is truly for, who gets to participate in its aesthetic, and who is excluded from its promise?

Fashion consistently acts as a technology of queer disobedience. Sometimes it is quiet and trembling, sometimes ecstatic and explosive. In Circle, it is a fragile secret. In Liminal Space, it dissolves the self. In The Sneeze, it stages joyful bodily excess. In Do I?, it queers tradition from within. Together, they argue that to queer the frame is to refuse the stability of the image, to let desire misbehave, and to allow identity to spill beyond its assigned borders. Fashion is the medium through which these refusals materialise: stitched, draped, glitched, and ruptured into being.

The Monstrous Feminine Takes Centre Stage

Paired with the queering of the frame, the monstrous feminine also dominated the screens across several of the films. It becomes a radical site of power: no longer a figure to be feared, contained, or corrected, but one that strips through the boundaries imposed by the patriarchy.

Each film mobilises the grotesque, the excessive, and the unruly body to reclaim femininity from purity myths, beauty standards, and generational control. Through fashion, ritual, and bodily rupture, the feminine monster emerges as both a political weapon and a mode of liberation.

Starting with Motherfocking Art, myth and cartoonish chaos is used, weaponising the everyday grotesque: period blood. In a hyper-stylised photoshoot drenched in bright florals and male-gaze expectations, femininity is tightly policed, where bodies must be slim, appetites suppressed, faces seductive. The menstrual cup leak exposes the lie of this controlled femininity. The menstrual cup is a hyper-modern representation of sustainability, viscerality, and femininity, or a contemporary version of the grotesque body, where women are visually witnessing their blood collected in a cup to its fullest. This acts as a direct contrast to the outdated shame surrounding periods. Blood becomes not shame, but rebellion.

The film turns taboo into slapstick catharsis. The women, their dresses covered in menstrual blood, embrace each other joyfully, directly denying the photographer’s disgust and his oblivious “Not my problem.” They then destroy the set, topple the structures that reshape their bodies through Photoshop, and, in a final absurd flourish, one of the women suffocates the photographer with her vagina. Fashion becomes chaotic, messy, soaked in bodily fluids: a refusal of aesthetic sanitisation. The closing scene, where the women lovingly articulate their insecurities, reframes the monstrous body as celebratory and whole.

Scapegoat tackles the same theme of rebellion, but against a more hidden, sinister oppression. It reimagines the monstrous feminine through ritual, lineage, and bodily choreography. Drawing heavily from the 2018 adaptation of Suspiria, the film stages a battle between the oppressive mother-figure, draped in red, eyes white with supernatural power, and her six daughters trapped in tight, skin-toned garments that mark them as extensions of her will.

Clay, rope, and dance become tools of both domination and liberation. The daughters knead grey clay in a circle, moulding identity under surveillance before the mother violently disrupts their creations. The six daughters eventually revolt, binding the mother in clay and hay, placing a horned crown upon her body, leaving her as a fallen deity. This constitutes a symbolic act of matricide, severing the lineage of internalised control. Fashion here is ritualistic and corporeal, grounded in earth-tones, ropes, and the stark contrast of the mother’s blood-red costuming.

Finally, The Feminine Urge is the most explicit reclamation of the monstrous feminine, presenting a visual litany of archetypes: Offspring; Madonna and the Whore; Doctor; Vagina Dentata (“toothed”); Mater Gregiorum (roughly “Mother Gregory”); and The Archaic Mother. All mutated into something definitely uncontrollable. Drawing from the Christian iconography, the film escalates from purity to grotesque excess: a baptism pool becomes a site of possession; a white wedding gown splits open to reveal a red bodysuit pulsing like exposed veins; the body becomes sacred and obscene at once. Another example is the term “Mother Gregory”, which could mean a mother figure associated with authority, ritual, or patriarchal lineage, as Gregory is historically a papal name, hinting at religious or institutional power.

The fashion is sculptural, ritualistic, and biomechanical: lace and lingerie reinterpreted as anatomical exoskeleton, bridal fabric folded into organs, bodysuits adorned with hoof-like extensions. Figures with insect teeth, multi-breasted matriarchs, and chainmail chastity garments transform femininity into a mythic horror vocabulary. In the end, blood, ooze, wounds, and moans crescendo into cathartic screams. Rather than offering coherence, the film insists on multiplicity (“We are many”) and uses horror to liberate femininity from the burden of interpretation.

Other Notable Films

The FASHIONCLASH film program also presented all other participant films. On 15th November, the additional films were presented in a smaller, quieter cinema room. There was no premiere nor award ceremony, just a humble screening with a polite audience. Two films left a significant impression on me that night: Mannman Chadwon by Gwladys Gambie and Tracing Roots by Claire Tsumura.

Mannman Chadwon is a poetic, dreamlike ode to fantastic femininity rooted in Afro-Caribbean imagination. It is a striking film with its use of graphic series style: social portraits intertwined with botanical elements and symbolic patterns. Following the evolving red silhouette of the creature “Mannman Chadwon,” the film traces a symbolic journey from birth to liberation, portraying feminine transformation within a destructive patriarchal world. Gambie’s artistic language draws heavily on plants, landscapes, and Creole mythology, creating an oniric, sensuous universe where fantasy and resistance merge.

The imagery is lush and metaphorical. The botanical forms, especially the coconut tree, function as archetypes expressing domination, colonial memory, sexuality, and power. What is particularly interesting about the imagery is the black-and-white colouring turning into a consistent red hue glaze over the scenes of nature. Such a contrast highlights themes of conflict, duality, and complexity of social histories.

Fashion blends natural textures with motifs inspired by Afro-Caribbean heritage, operating both as an erotic surface and a site of tension shaped by colonial histories. Vibrant tropical hues are muted by red tones, while patterns echo the complexity of the social and political legacies embedded in Caribbean culture. Through this hybrid aesthetic, the film becomes a revolutionary hymn to life and freedom, where femininity continually reshapes itself in defiance of the systems that seek to confine it.

You can watch Mannman Chadwon here.

Mannman Chadwon roots its exploration of identity in mythic, Afro-Caribbean femininity and liberation. Tracing Roots carries this inquiry inward, shifting from collective ancestral transformation to a more intimate journey of diasporic self-reconciliation.

Tracing Roots is a meditative exploration of identity, diaspora, and cultural disconnection, conveyed through symbolic imagery, expressive movement, and a spiritual atmosphere of introspection. The film invites us into a reflective emotional landscape, echoing themes of gratitude, apology, and reconciliation with one’s lineage and lived history.

Tracing Roots’ aesthetic includes contemplation and serenity, infused with mindfulness and inner searching. But then the scene shifts to a dark setting, a red circle painted on a floor, and a white chalk man covered in red strings lying in the middle. The soundtrack charted the emotional arc, one of the most compelling rhythms and sounds I have personally experienced, evoking tension and supporting the film’s emotional narrative, moving from serenity to turmoil.

Fashion remains understated and rooted in the spiritual setting, reinforcing humility, simplicity, and presence. The film then moves back to serenity, enhancing the contemplative mood throughout this segment. Subtitles help carry the emotional weight of repeated phrases such as “Thank you” and “I’m sorry,” suggesting a narrative of healing and reconnection after rupture (“after the stolen vow”).

Through deliberate editing and symbolic language, Tracing Roots becomes an intimate, open-ended reflection on diasporic self-discovery, allowing each viewer to locate their own emotional truth within its quiet, searching spaces.

You can watch Tracing Roots here.

You can find the rest of the films in the Fashion Film Program here.

The Future of European Fashion Film

The Class of 2025 positions Maastricht as a hotspot for experimental fashion cinema. Their films suggest a future in which fashion film becomes narratively ambitious, politically engaged, and accessible to global, multilingual audiences across multiple genres. The emergence of feminist horror, queer surrealism, and class-conscious aesthetics signals a generational shift.

This is the year fashion films became fearless within FASHIONCLASH.

Comments