Game of Votes: Who is ruling the Netherlands?

- Augustin Forjonel-Legrand

- Sep 6, 2025

- 6 min read

Second Take

The Netherlands heads to the polls again, earlier than expected. If you missed the headlines this summer, you should know that parliamentary elections are scheduled to take place in the Netherlands on October 29, 2025. Originally, the next general election was planned for 2028, but this was without accounting for the collapse of Dick Schoof’s governing coalition last June, after the withdrawal of Geert Wilders’ Partij Voor de Vrijheid (PVV, far-right party).

4 parties were part of this right-wing alliance: the farmer-led BBB, the centre-right VVD, the centrist NSC, and Geert Wilders’ far-right PVV. This surprise announcement followed a disagreement over asylum policies, a core issue for the coalition since its introduction in 2024. On June 3, 2025, Geert Wilders posted a short message on his social media that caused an earthquake in the Netherlands: “No signature for our asylum plans. No amendment to the agreement on the broad outlines. The PVV leaves the coalition.” Automatically, this already fragile coalition collapsed, and new elections were called.

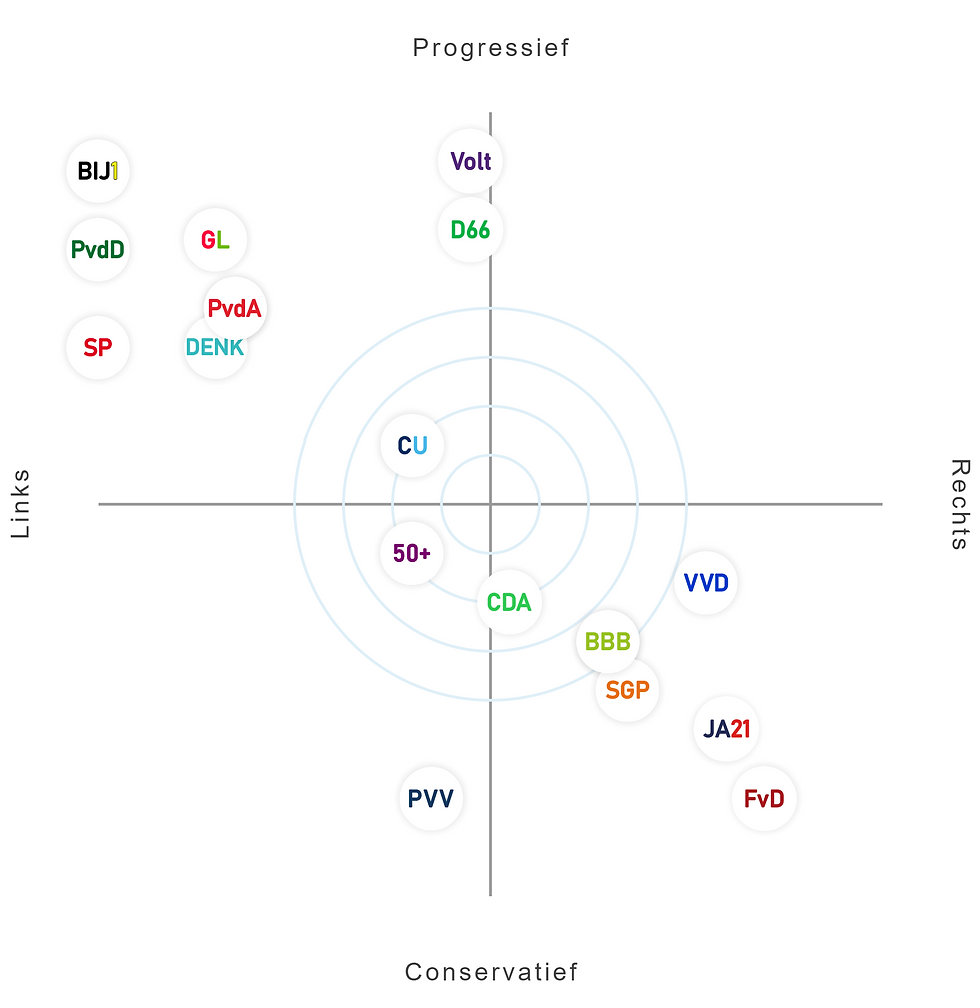

*PVV appears on the left part of the chart due to a few elements of its economic program, based on the evaluation criteria of Kieskompas. Still, the party remains nationalist, anti-immigration, and Eurosceptic. Its very aggressive campaign on immigration, as demonstrated later in this paper, is an example of its far-right positioning.

Rules of the Game

In these elections, Dutch citizens aged 18 or older vote for their representatives who will sit in the Tweede Kamer (Second Chamber), which is the “House of Representatives”. The First Chamber (“Eerste Kamer”) is the Dutch Senate. This institution doesn’t propose laws but reviews bills, and is elected by provincial councils.

The Tweede Kamer is composed of 150 seats, which are proportionally distributed among the parties, according to the number of votes they receive. In the Netherlands, the system is based on the rules of representative democracy. For this reason, the election system is a national party-list proportional system, meaning that people vote for a person on the list (most of the time, the top candidate), but they could also choose to give their ballot to a specific candidate. If a candidate is far in the list order but benefits from strong popular support, it can jump over positions in the list and be elected. The lists are the same for the whole country. This allows popular candidates who may be low on the party list to be elected, reflecting voter preference more directly.

After the elections, seats are distributed proportionally among parties. A political party needs to reach a 0.67% threshold of total votes to receive a seat, according to the D’Hondt method. This system of proportionality often results in a fragmented Tweede Kamer. Thus, negotiations take place for several weeks to find a compromise between the parties on a common program to form a government coalition.

Marc Vervuurt, city councillor in Venlo and candidate for the centrist-liberal party D66, explained this mechanism to me during an interview. “The party that gets the most votes is responsible for the coalition talks. Parties know that they won’t be able to achieve their whole program. We need to be ready to make concessions.” As said earlier, the last coalition was composed of four parties. Wilders’ PVV won the elections with 37 seats in the Tweede Kamer, and it took more than 7 months (223 days) to form the coalition.

State of Affairs

What is the situation at the time of writing? According to an August 26 poll published by the reliable Dutch media outlet “EenVandaag”, and relayed by Euronews, the far-right party PVV is predicted to win with 33 seats. Behind them, the left-wing coalition “GroenLinks-Pvda” (Greens and socialists), led by the Maastricht-native and former VP of the European Commission Frans Timmermans, is ranked second with 26 forecasted seats. According to De Telegraaf, the CDA keeps rising in the polls, and both parties are given very close in the ballots.

The biggest loss in the polls during the summer was for the right-wing VVD, led by Dilan Yeşilgöz. Indeed, according to the NL Times and NOS, the party leader accused the Dutch singer Douwe Bob of anti-semitism after he refused to perform “at a Jewish football tournament” (NOS) due to the presence of “Zionist posters and pamphlets displayed at the venue” (NL Times). Yeşilgöz’s allegations were unfounded, but she posted a message on X to denounce the singer's attitude. Facing “serious threats”, Douwe Bob decided to leave the Netherlands for a couple of days. In the meantime, he asked the VVD’s leader to delete her tweet, which she refused to do. As a last resort, Bob filed two complaints for “libel, slander, and insult” and reached out to the Public Prosecution services in Amsterdam. Finally, the party issued a communique, agreeing to withdraw the tweet and apologizing for their reaction. Still, this controversy affected Dilan Yeşilgöz's image, as evidenced by her decline in the polls (cf EenVandaag).

As explained by Euronews, the downfall of the centre-right VVD (the party of former Prime Minister Mark Rutte) contributed to the rise of the right-wing CDA party. This Christian-Democratic alliance is forecasted to win between 20 and 23 seats. The leader, Henri Bontenbal, is gaining in popularity. Indeed, according to an article published in The Telegraaf, Bontenbal is “primarily praised for his 'constructive and anti-polarizing attitude.’ For 66 percent of CDA voters, he plays an important role in their vote.” In the same article, an Ipsos poll issued on September 3 announces that CDA is now neck and neck with GL-Pvda.

“The CDA is on the rise and likely to be part of a future government.”, said Vervuurt. For him, based on the actual situation, the coalition will comprise four parties: GL-PvdA, CDA, VVD, and D66. “The political landscape is very divided, and we need to be ready to cooperate. This coalition will be composed of the left and the right, something that is more stable than the former coalition. In D66, we are willing to cooperate with constructive parties.” This coalition’s composition is seen today in Germany, where the CDU Friedrich Merz is the chancellor and his party works with the Socialists in the coalition.

In the actual state of things, the far-right is not expected to enter the coalition, according to Vervuurt. “We used to have a 'Brandmauer' or a 'Cordon Sanitaire' until two years ago. Today, this is something that most of the political parties want back. We understood that working together with the PVV brings instability.” He explained to me that the leader of the party that arrives first in the elections is the one who is expected to become Prime Minister and to organize the coalition talks.

Still, even if the far-right is not a favorite partner for the coalition, Marc Vervuurt thinks that they will impose their campaign themes in the political debate: Asylum policies, immigration, and national security. Indeed, Euronews explains that the “party advocates for a complete stop to immigration, wants to close migrant reception facilities and to send back asylum seekers at the border.” Geert Wilders, who has been leading the PVV since 2006, has entered this campaign with a strict program on these topics and a very aggressive tone. An example of this is the social media post that he published in early August (related in Euronews’ article), showing two half faces: on the left, a blond woman with blue eyes and a smile, with the letters “PVV” underneath her face. On the right side, an older woman, looking angry, is wearing a headscarf and has the letters “Pvda” under her portrait. This shows to what extent the far-right campaign promises to be aggressive against the left. 14 Muslim women's associations have filed a complaint against Wilders, accusing him of discrimination and inciting hatred, according to the NL Times.

Young Voters, Big Shifts

“Until now, people were on summer holidays and didn’t have their minds on politics”, said Vervuurt with a little smile. “The campaign will start in the first half of September, and we are 200% ready to engage in it.” Throughout the interview, I understood that he thinks, like a lot of people in the Netherlands, that these elections are a chance to go over these years of far-right government. My last question was “How to encourage a young Dutch citizen to vote in these elections?”. Vervuurt said that “a far-right government can break things very quickly, and that it is hard to rebuild things afterwards.” He also said that it damaged the country's international reputation. “We need to encourage youth to have a new hope in political power. We need their energy and their ideas to contribute to our project.”

According to a study from EenVandaag published on September 3, “4 out of 10 young people don’t feel attracted by any political party”. This study was done with the participation of more than 1,300 young Dutch voters (aged between 16 and 34). This article also explains that “53 percent of young people feel that political parties listen to them.” They argue that parties focus only on short-term issues. As the Netherlands faces another turning point, it is time to ensure that the voices of young people have an impact.

Comments